Related

Stay up to date with our work

Our monthly updates are a great way for you to stay up to date with our work, events, and higher education news.

Last updated on Friday 19 Apr 2024 at 11:29am

On 31 October 2021 more than 190 world leaders will gather at the UN’s Climate Conference (COP26) in Glasgow to agree actions limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees.

The consequences of not keeping to 1.5 degrees are immense: we will experience more extreme weather, with increased flooding, droughts and storms. Human activities are responsible for the increase in temperatures through the way we use power and travel – so changing how we live is key.

Professor Paul Harrison, Pro-Vice Chancellor for Innovation and Engagement at the University of South Wales, has said that ‘the biggest challenge is the breadth of behavioural, operational and physical change which we need to achieve.’ How do we achieve this amount of change? We must understand what is happening to our environment, how our actions harm it, and develop new technologies to replace harmful ways of living and working.

The biggest challenge is the breadth of behavioural, operational and physical change which we need to achieve.

Professor Paul Harrison

Pro-Vice Chancellor for Innovation and Engagement, University of South Wales

Research must inform the actions of decision-makers. Climate scientists at the University of Reading played a leading role in the 2021 United Nations report which showed the world is not on track to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees, a finding that will drive negotiations at COP26. Research should also inform those making decisions every day across nations and at the regional and local level. The University of York is establishing an environmental sustainability academy which will help share knowledge with the city of York and across North Yorkshire.

Current and future decision-makers must understand climate and sustainability and have the right skills to lead change. So will those who work in the green jobs of the future. The education that universities provide is critical to equipping today and tomorrow’s workforce to make a difference. Universities are embedding sustainability into the learning opportunities for students. At the University of Gloucestershire, all students have the opportunity to undertake a sustainability internship or placement, and their music students have delivered carbon footprinting with Live Nation festivals.

Students from the University of Gloucestershire at Download festival

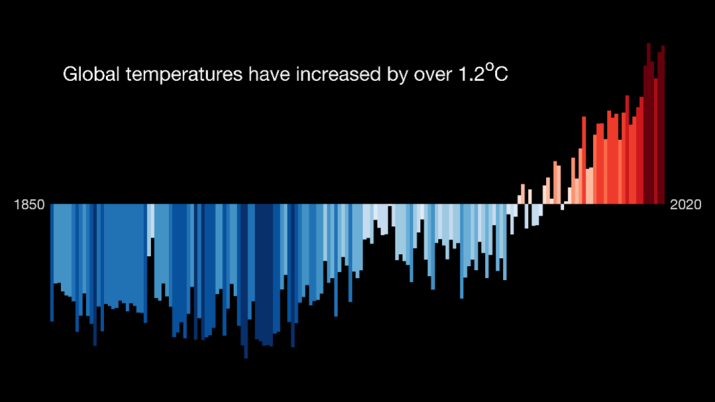

Source: Professor Ed Hawkins, University of Reading #ShowYourStripes

Many universities are marking COP26 with initiatives to develop the climate leaders of tomorrow. The University of Newcastle will support over 200 undergraduate students to work on research projects that address the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. The University of Sussex will support students with outstanding climate leadership to work with the local community. Nottingham Trent University will offer bursaries to students from disadvantaged backgrounds and guide recipients to advocate for improvements in their community and beyond.

As well as the education and research they provide, universities must lead by example through how they operate and develop their campuses. Students play an important role in holding their universities to account, with over 90% of 1200 students surveyed concerned or very concerned about climate change.

Many universities have improved their energy efficiency, invested in new technologies and are sourcing energy from alternative sources. For Professor Julie Sanders, Deputy Vice-Chancellor of the University of Newcastle, ‘the awakening to the climate and ecological emergencies has been inspiring.’ For example, Keele University agreed a 25 year deal with ENGIE, a leading energy and services company, to develop a wind, solar and battery storage park to generate 50% of the university’s power.

The solar farm at Keele University

Many universities have already set net zero targets – but not all. Our climate task and finish group, chaired by Professor Judith Petts, Vice-Chancellor at the University of Plymouth, has led our members to commit to setting targets which support the government’s plans for achieving net zero by 2050 at the latest (or devolved government equivalents) and to report on these targets transparently and consistently.

Setting targets alone is not enough – they must be backed by action. Achieving ambitious net zero targets requires universities to make difficult decisions that impact on their ability to deliver education and research. ‘Priority actions are not always ‘popular’ actions,’ says Professor Petts. ‘Identifying and investing in priority actions that will have the most impact is complex.’

Overseas travel and recruitment of international students may support a university’s global ambitions, but work against its sustainability goals. Funding for decarbonisation means money not used for student services, or research, or teaching. Universities must look to the long-term and make these difficult trade-offs. ‘We cannot achieve our goals at the expense of the environment,’ says Sir Anton Muscatelli, Principal of the University of Glasgow. Glasgow was the first UK university to declare in 2014 that it would divest from fossil fuels within a decade.

The scale of investment needed to achieve net zero targets is substantial. ‘Measures that will save us money and improve our environmental impact over the long term can involve significant up-front costs,’ says Professor Frances Corner, Warden of Goldsmiths, University of London.

While Goldsmiths was successful in accessing funding from the public sector decarbonisation scheme to help install a new low-carbon heat network, many other universities have missed out. Barriers to accessing public funding for decarbonisation, such as short timescales required for project delivery, need addressing if universities are to meet the costs of achieving their net zero ambitions – without an adverse impact on their ability to deliver high quality teaching and research.

Measures that will save us money and improve our environmental impact over the long term can involve significant up-front costs.

Professor Frances Corner

Warden of Goldsmiths, University of London

Stable funding for teaching and research from government is also essential. This will not only allow universities to invest in the longer-term changes needed on their campuses, but it will enable universities to educate future climate leaders and make the breakthroughs needed to combat the world’s most pressing sustainability challenges.

It is impossible to address the climate and ecological emergencies alone. Collaboration is needed – between universities to share best practice, and between universities and their local city and regional partners to address common issues. For example, Staffordshire University works with their local authority to increase biodiversity and on green energy. Northampton University is working in partnership with Northampton General Hospital and the local authority to achieve net zero by 2030.

Universities and the government must also trust each other to work together effectively. It has been positive to see how government has worked with the COP26 Universities Network in the run up to COP26. But many wish to see greater government backing of the sector’s sustainability ambitions and alignment between policy making and research breakthroughs.

Matched funding by government for COP26 scholarships that universities provide would be an important signal that there is a joint commitment to developing the next generation of climate leaders. The development of a government sustainability strategy for education is an excellent opportunity to empower universities to deliver the changes that are vital to all of our futures.

Our monthly updates are a great way for you to stay up to date with our work, events, and higher education news.